Puppet theatre is a radical art that has succeeded in mixing the old with the modern, has served many social functions including storytelling, spreading the news, passing norms and values, criticising political matters and healing. It has been addressed to any kind of audience, children and adults, poor and rich, it has been played on the streets, public squares, and carnivals and at wealthy households. Its first materials can be the cheapest or the finest, it doesn't need a lot of words to address its intentions. Whether the character depicted is Charles Quint or a villager, the policeman or the villain, the puppet theatre owes much of its radicality in the fact that it can be multifaceted, inclusive and heterogeneous.

The art of puppetry is a very ancient one. In England, for example, there is evidence of marionette shows dating back at least 600 years. In the medieval times, minstrels played their shows with glove puppets. The Romance of Alexander, written in Flemish is a 14-century manuscript depicting images of glove puppet shows. The first puppet shows might have represented Greek and roman myths or stories from the bible. The medieval clergy used puppets to preach Christianity and a devil figure surrounded by fireworks was used to inspire fear and awe to the crowd. There is also reference in the Shakespeare's plays to the puppet theatre. In the 17th century Italian minstrels were coming to Britain to perform at open spaces with string puppets. At the same epoch, a very popular theme were religious stories such as Jonah and the Whale but also some political stories were narrated based on current events such as Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder plot. In mid-17th century in England, during the time of religious and political upset, theatres were closed, but shows performed with glove and shadow puppets “enjoyed a short of immunity” and they flourished.

After the end of the Second English Civil War in 1648, puppet players came from Europe, bringing with them a string puppet based on Italian Commedia dell'arte, Pulchinella. That thuggish character passed to the English tradition as Punchinello, later “Punch”. A similar character integrated in other European cultures, called Kasperle in Southern Germany and Austria, Polichinelle in France and Petrushka in Russia. In Belgium, Puppet Theatre was loved by the people. According to folklorist Antoine Demol, Philippe ΙΙ of Spain, son of Charles Quint, forbade theatres because he was not really loved by the people and he was afraid that theatres would become spaces of political upheaval against him. Nevertheless, marionette shows went on. Thus, Brussels replaced the theatre actors with poechenelles (polichinelles) and they performed puppet shows in secret theatres.

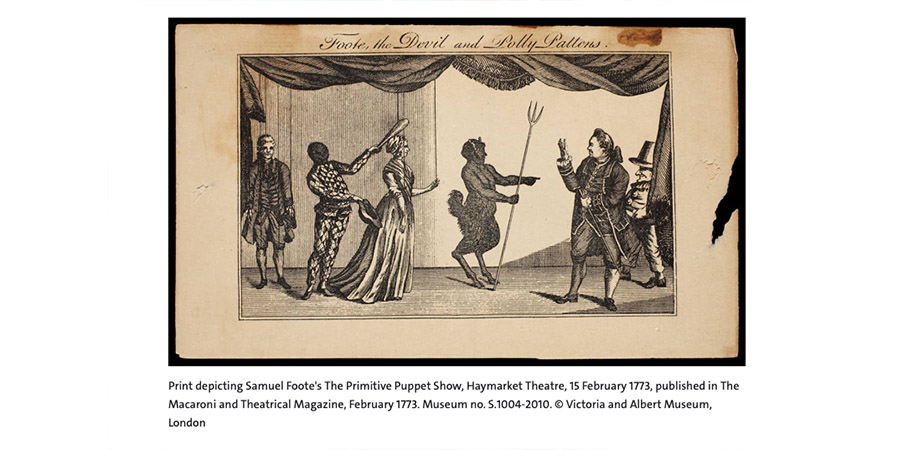

During 18th and 19th century, Puppet Theatre thrived in most European countries. In 18th-century London marionettes were popular among the adult audience and a favourite theme was the satire of famous people and of the theatrical fashions of the era, such as Italian opera. In Brussels, at the beginning of 19th century, marionette theatres amused adult audiences in working-class neighbourhoods. At that time, they used mostly rod marionettes: a metallic piece was attached to the figure's head and strings permitted movement to the hands. Several assistants manipulated the marionettes and the showman interpreted the voices while watching the audience. The spectators expressed their emotions and showed directly their disdain for the characters that they didn't like, throwing stuff at them. At the same time, in Sicily for example, puppet shows were performed at bourgeois households in order to transmit values and morals to children.

And what about marionette's political aspect? One could claim that puppets represent the most fragile social groups, manipulated by the powerful. When puppetry gets out of the drawing-room it loses its refined form and behavioural norms. In public spaces it often serves political purposes, and when it does so, it is not a flattering art. It is demeaning, sarcastic, exposing social ills. It represents the daemons of society, not its institutions. It is an art which is easier researched in police records than in theatre chronicles. It would be also interesting to notice that marionettes were used to spread political propaganda whether in favour of or against certain kings, political actors, parties, ideologies. Expressing support or hostility towards a certain regime could be a very risky act and puppeteers were always ready to pack their puppets and flee when they were chased by the authorities.

Puppetry is subversive and liberating, and it owes those characteristics partially due to the fact that its sculpture works as quasi-narrative, thus it takes less of language and more of action. Also, puppeteers enjoyed an asocial status that enabled their art to grow. Guignol, a French puppet invented in 1808 in Lyon by Laurent Mourguet, is a working-class character representing all the good and bad stereotypical characteristics of people of his class: he is overeating because he goes hungry often, he is violent but never means harm. Guignol's depiction is the personification of a primitive expression of emotions. This mondus operandi is focused on conflicts, anxieties, pleasures, and primary functions such as food, sex, death and fears. French psychoanalyst Octave Mannoni would see in this depiction the manifestation of the id. Those folksy, working-class characters consolidated feelings of collective identity and belonging.

Dimitra Kournianou

Trainee HICDB

Napoleon's marionette,

Halle Gate museum in Brussels

References:

- 1. The radicality of the puppet theatre, Peter Schumann, 1990

- 2. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-history-of-puppets-in-britain#slideshow=21816336&slide=0

- 3. https://wepa.unima.org/en/society-and-puppets-social-applications-of-puppetry/

- 4. https://wepa.unima.org/en/guignol/

- 5. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Théâtre_royal_de_Toone

- Tags:

- Articles

- Dimitra Kournianou